The Torah reading for Shabbat of Passover is not thematically surprising: it recounts the Moses’ demand to see God’s… well to see something of God that would allow him to SEE his Master in a way that was intimate, close, that would grant withheld closeness and understanding. It isn’t clear exactly what it is that he’s asking to see, and of course when communications of this sort do take place between two sentient beings the communication is nonverbal so whatever transcription set down in the text we now read is attempting to communicate, it is already far removed from the interaction it describes. Still we know that Moses is demanding some sign of special intimacy. God tells him He will give him this, but that he cannot show Moses His face because no mortal can see It and survive. Instead he “passes his goodness” over Moses while Moses shields himself in a nook in the rocks of the mountain where the two are communing. Moses hides himself inside the rock and then immediately after this the text cuts to Moses hewing tablets out of rocks to set down precepts for the people. Among the precepts is the commandment to keep Passover along with a host of other festivals. It is obvious that we are reading this particular text on this particular day because of the Passover bit.

Okay. BUT. I was intensely struck by this strange juxtaposition: Moses demand for unity with God wholly separate, blessedly removed from the rest of the people. Passover is our origin story. It is not about Moses. It is not about his intimacy with God. On the contrary, intimacy is not a relevant quality in the relationship with God which is communicated through the Haggadah and the rest of the passover rituals and practice. The seder is about the forging of a nation. The different typologies presented in the Haggadah are all different kinds of Jews who relate to one another and their nation generally in different ways. No one has a private relationship with God at the seder. In fact, most of Jewish liturgy is in the first person plural. Hardly any Jew (using the word loosely) in the Bible save Moses has a relationship with God that isn’t first and foremost about the Jewish Nation. Even Joseph is ultimately a political and social figure. He does not long for communion with God despite having bizarre attunement to Him.

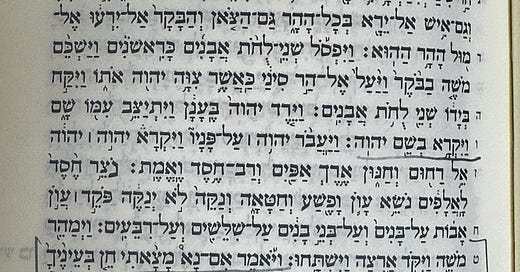

Leni and I were reading the text together this morning and I was trying to communicate to her the strange fact that the fact that a prophet is capable of acting as emissary between God and Man does not mean that prophet is particularly interested in the content of the message he is relaying. The capacity to grasp a truth that no one else can grasp does not mean you are especially interested in the content of that truth. And in some sense being a prophet is necessarily a great burden because the appellation itself assumes that the person capable of grasping an inarticulable truth is also yoked with the responsibility of removing himself from the intimate, private space — the nook in the rock — in which he was able to commune with that Truth, and then go back down the mountain to the awaiting mass and attempt to communicate the inarticulable. Someone who could understand the truth but was able to just stay up on the mountain wouldn’t be a prophet, and wouldn’t consider the truth a burden. “Isn’t that the difference between prophecy and mysticism?” Leni asked.

I thought that was a brilliant question.

Shabbat Shalom!